Dopamine D2 Receptor Downregulation Marks the Difference Between Drug Addiction and Compulsive Behaviors (Dopamine 5)

- Hermes Solenzol

- Nov 30, 2025

- 14 min read

Pleasure is not addictive and does not decrease mental energy

Dopamine D2 receptor downregulation is the hallmark of addiction

In the previous article in this series, I showed that the downregulation of dopamine D2 receptors is the hallmark of drug addiction. This view is widely shared by investigators of addiction (Trifilieff et al., 2013; Trifilieff and Martinez, 2014; Volkow and Morales, 2015).

All addictive drugs downregulate the D2 receptors. Non-addictive drugs, like cannabis or psychodelics, do not downregulate D2 receptors.

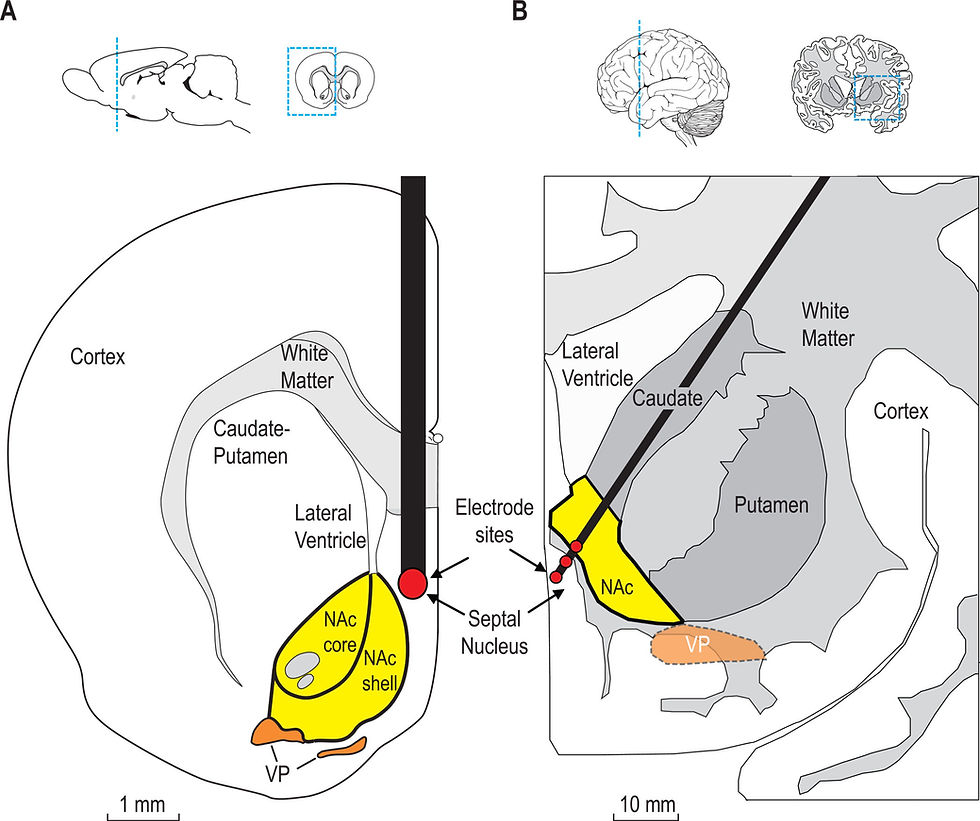

D2 receptors in the medium spiny neurons (MSNs) of the indirect pathway, which connects the nucleus accumbens with the frontal cortex, are essential to maintain motivation, sustained effort and focused attention. Therefore, we could consider them the molecular foundation of mental energy.

Without enough D2 receptors, drug addicts live in a state of dissatisfaction and lack of motivation. They lack mental energy or, rather, all their mental energy is consumed by drug seeking.

With this in mind, we can answer the questions of whether some behaviors, like sex, gaming or exercise, are 1) addictive and 2) decrease our mental energy. If so, they should downregulate the D2 receptors, like all addictive drugs do.

The controversy: are behaviors addictive?

People who think that some behaviors are addictive often refer to a review paper from 2011 (Olsen, 2011). Table 1 of that paper summarizes the information in this regard and has been reproduced in Wikipedia. That table is a good source of references concerning the evidence that behaviors are addictive. In the columns, it lists five things that are supposed to induce addiction:

opiates,

psychostimulants (cocaine, amphetamines),

food high in fat and sugar,

sex,

exercise, enriched environment and sensory reinforcement.

Opiates and psychostimulants are stereotypical addictive drugs, so they are a good positive control for addiction.

It’s nice to have sex in its own separate category.

An enriched environment (see image) means that rats or mice are housed in cages containing toys, running wheels and other rats or mice (McCreary and Metz, 2016). It has been shown to increase the intelligence and lower the stress of the animals.

Sensory reinforcement means that the rats or mice are exposed to novel sensations, like new objects, food or smells.

Exercise, enriched environment and sensory reinforcement shouldn’t be lumped into a single category, since they may have different effects on the brain. However, they are unquestionably healthy, so they could serve as a control for things that should not be avoided. Still, the authors make it clear that they consider them too addictive behaviors.

Item 3, food high in fat and sugar, is the most tricky category. Some foods may be addictive because they produce spikes in insulin, a hormone that seems to have pronounced effects on the reward pathway (Davis et al., 2008).

Let’s now examine the different items on the rows of that table, which are proposed as markers of addiction. I exclude items that do not apply to sex and exercise / environmental enrichment / sensory reinforcement because they are not relevant to this discussion. I also exclude things that have opposite or inconsistent effects between opioids and psychostimulants, since they are not good markers of addiction.

Downregulation of D2 receptors is in the 8th row of the table. As I stated before, opioids and psychostimulants downregulate them. So does food rich in fat and sugar. However, exercise / enriched environment / sensory reinforcement upregulate the D2 receptors, that is, they do exactly the opposite of addictive drugs. The entry for sex in empty.

Cross-sensitization with psychostimulants, psychostimulant self-administration, and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior are listed as markers of addiction in three other rows. Here again, exercise / enriched environment / sensory reinforcement have effects opposite of those of psychostimulants and opioids. This means that these behaviors decrease the interest in addictive drugs, that is, that they have anti-addictive properties. This is hardly compatible with the idea that these behaviors are addictive.

CREB phosphorylation decreases and delta-FosB increases in the nucleus accumbens head two other rows. They are affected similarly by addictive drugs and exercise / enriched environment / sensory reinforcement. However, these are general markers of neuronal activation. It makes sense that these three things activate neurons in the nucleus accumbens, because they activate the reward pathway. Exercise requires motivation. Sensory stimulation and a rich environment prod the animal into action.

In summary, exercise / enriched environment / sensory reinforcement have opposite effects from drugs on D2 receptors and drug seeking behaviors. This shows that these behaviors are not addictive, and even have anti-addictive properties.

A study examined social media “addiction” (Fournier et al., 2023) as defined by six components: salience, tolerance, mood modification, relapse, withdrawal and conflict. It found that these six components are not consistent with each other and are not associated with mental problems.

Exercise

Some scientists consider exercise addictive (Olsen, 2011; Dinardi et al., 2021).

However, exercise has been known since the 80s to increase D2 receptors in the rodent striatum (MacRae et al., 1987; Bauer et al., 2020). In rats, High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) increased D2 receptors, but not D1 receptors, in the shell of the nucleus accumbens (Tyler et al., 2023).

In humans, the results are less clear. In two patients with early Parkinson’s disease, treadmill training for 8 weeks increased D2 receptors, measured with [18F]fallypride PET imaging (Fisher et al., 2013). Another study in older subjects using PET with the D2/D3 receptor ligand [11C]raclopride (Jonasson et al., 2019) found that aerobic exercise did not increase D2 receptors. A study of 19 methamphetamine users with [18F]fallypride PET imaging found that exercise for 8 weeks increased striatal D2 receptors in the exercise group but not the control group (Robertson et al., 2016). This shows that exercise can be used to reverse the downregulation of D2 receptors produced by drug addiction.

Gambling

Pathological gambling is the stereotypical compulsive behavior, the only behavior classified as addictive in the DMS-5 (Clark et al., 2019).

However, gambling did not change the amount of D2 or D3 receptors in the striatum or the substantia nigra (Boileau et al., 2013). In this human study, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging was used to measure the binding of an agonist of D3 receptors (PHNO) and an agonist of both D2 and D3 receptors (raclopride). No differences were found between 13 pathological gamblers and 12 control subjects.

A review of human studies (Clark et al., 2019) found no changes in D2 receptors in gamblers. In addition, MRI imaging found only small changes in gray and white matter in gamblers, while these changes are major in drug addicts. Functional MRI found some changes in the ventral striatum and the medial prefrontal cortex, but the direction of these changes was not consistent between studies.

Therefore, the neurophysiological profile of gambling is completely different from drug addiction.

The D2A1 variant of the human D2 receptor is involved in addiction

The human D2 receptor gene has several variants, which produce D2 receptor proteins with different functions. In particular, the Taq A1 variant (D2A1) is commonly found in drug addicts and alcoholics (Comings and Blum, 2000). It has been proposed that the reason for this is that individuals with this variant have an abnormal reward pathway, something that has been called reward deficiency syndrome (Blum et al., 1996; Comings and Blum, 2000). The D2A1 variant decreases the amount of D2 receptors and produces less cognitive flexibility (Fagundo et al., 2014).

Pathological gambling is also associated with the D2A1 variant of the D2 receptor. In a genetic study (Comings et al., 1996), 50.9% of the subjects with gambling disorder carried the D2A1 variant, compared with 25.9% of controls. The severity of the gambling disorder correlated with the expression of the D2A1 variant.

This supports the idea that having less D2 receptors causes compulsive behaviors. While addictive drugs downregulate the D2 receptors, in gambling the decrease in the D2 receptors is not due to the behavior itself, but to genetic causes.

Does sex downregulate D2 receptors?

With all this in mind, we can address the questions of whether sex is addictive or causes a decrease in mental energy.

Unfortunately, I could not find any studies on the effect of sex on D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens. One study in rats (Nutsch et al., 2016) found that sexual experience increased the number of neurons with D2 receptors in the medial preoptic area of the hypothalamus, a brain region in which dopamine and D2 receptors trigger copulation (Melis and Argiolas, 1995; Giuliano and Allard, 2001; Nutsch et al., 2016). It is possible that sex also upregulates D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens.

In fact, sex has much in common with exercise, enriched environment (which includes social interactions) and sensory stimulation, activities that upregulate D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens. Even gambling, the model “addictive” behavior, does not downregulate D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens.

Therefore, we could infer that sex either has no effect or upregulates D2 receptors in the reward pathway. If so, sex should not be addictive or decrease the mental energy mediated by the reward pathway.

Effects of dopamine on sex

Dopamine, acting on D2 and D4 receptors, has stimulatory effects on all phases of sexual activity: arousal, erection and copulation (Mas et al., 1990; Komisaruk et al., 2006; Melis et al., 2022). In men, the non-selective agonist of D1 and D2 receptors apomorphine has been used to treat erectile dysfunction (Giuliano and Allard, 2001). In female rats, dopamine facilitates sexual arousal and orgasm (Uitti et al., 1989; Shen and Sata, 1990).

However, these effects of dopamine on sex are primarily mediated by hypothalamic neuronal pathways, the incertohypothalamic, the tuberoinfundibular and the hypothalamospinal systems (Melis et al., 2022).

Although dopamine is released in the nucleus accumbens during sex (Mas et al., 1990), the importance of this for sexual behavior is considered marginal (Paredes and Agmo, 2004). Let’s keep in mind that motivation for any behavior involves dopamine release in the reward pathway. Mice with a mutation that makes them unable to release dopamine in the nucleus accumbens lack motivation to do anything at all, including drinking and eating (Wise and Jordan, 2021).

Why is sex considered addictive?

Then, why do some scientists consider sex addictive? The evidence provided by Olsen (Olsen, 2011) is quite flimsy. He does not report any effect of sex on D2 receptors, psychostimulant self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. The main evidence he provides is the following.

Sex cross-sensitizes with psychostimulants, unlike exercise / enriched environment / sensory reinforcement. This means that rats addicted to cocaine have more sex. Conversely, rats that have more sex like cocaine. However, this doesn’t mean that the rats are addicted to sex. It could simply mean that once a rat is used to seeking a reward, it tends to do it more, no matter if the reward is sex or cocaine. Seeking a reward is not the same as being addicted to it.

Conditioned place preference is an experiment in which a rat gets an injection of a drug in one of two chambers. If the rat wants the drug, it will go back to the chamber where it was given the drug. If the rat doesn’t like the drug, it will avoid that chamber. A rat habituated to having sex chooses the same chamber where it has been given cocaine. Olsen takes this as an indication that sex is addictive, but this argument doesn’t hold to close scrutiny. Rats exposed to a rich environment also choose the chamber where they are given cocaine. However, not the rats habituated to exercise or to sugary food. Therefore, conditioned place preference is not a consistent indicator of addiction.

The L-DOPA paradox

As I explained in a previous article, L-DOPA is a precursor of dopamine that is given to Parkinson’s patients to alleviate their symptoms. Since L-DOPA bypasses the regulation of dopamine synthesis by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, it leads to a dramatic increase of dopamine in its synapses (Sulzer et al., 2016). Therefore, there is a greater release of dopamine.

The L-DOPA paradox is that, like all addictive drugs, L-DOPA produces an increase of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, but it is not addictive. What L-DOPA does, in some of the patients taking it, is increase compulsive behaviors, mostly hypersexuality, but also gambling, overeating and shopping (Potenza et al., 2007; Ceravolo et al., 2010).

One possible explanation for this paradox is that, in patients who take L-DOPA, dopamine is still released in short spikes by natural stimuli, while addictive drugs produce long increases in dopamine. It could be that what leads to addiction is the duration of the dopamine increase, and not its magnitude. This is consistent with the idea that D2 receptor downregulation is what causes addiction. A prolonged increase in dopamine would lead to the repeated internalization of the D2 receptors, causing their degradation. In contrast, the brief spike in dopamine produced by natural stimuli internalizes the D2 receptor just once, no matter how high the spike is, and this does not downregulate the D2 receptors.

This supports the idea that drug addiction and compulsive behaviors have different neurophysiological foundations. Still, the fact that L-DOPA increases compulsive behaviors (although only in a fraction of the people who take it) indicates that dopamine is involved in compulsion.

This supports the idea that drug addiction and compulsive behaviors have different neurophysiological bases. Although the fact that L-DOPA increases compulsive behaviors (although only in a fraction of the people who take it) indicates that dopamine is involved in compulsion, this seems to be an extension of its normal function rather than the radical and long-lasting alteration produced by addictive drugs.

Semantics or neuroscience?

It is undeniable that some people develop a strong compulsion to gambling, watching porn, shopping, using social media, exercising, among other behaviors. Then, why not say that these behaviors are addictive?

Perhaps this is just a semantic problem. Whether these behaviors are addictive depends on how we define addiction. If it is defined simply as developing a strong need towards something, then these behaviors could be considered addictive. However, the evidence that I show here indicates that this compulsion is not mediated by dopamine in the reward pathway, which is the main goal of this article series.

In contrast, drug addiction is characterized by profound, long-lasting alterations in the reward pathway. This includes D2 downregulation in the reward pathway, which is produced by all addictive drugs and explains the impulsivity found in drug addicts. Moreover, many compulsive behaviors have opposite effects to addictive drugs on cross-sensitization with psychostimulants, psychostimulant self-administration, and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior.

Giving the same name to two things with substantial neurophysiological signatures will lead to confusion. Therefore, I think it is better to reserve the name ‘addiction’ to substance use disorder, and to use ‘compulsion’ to name obsessive behaviors.

What cause compulsive behaviors?

If compulsive behaviors are not caused by alterations in the reward pathway, then what causes them?

It could be that compulsive behaviors are just habits that are difficult to break. Habits are automatic behaviors triggered by clues in our environment. The reward pathway plays a role in learning the association between the clue and the behavior, but this happens with any habit, good or bad.

Social isolation, stress, boredom or strong beliefs may drive some individuals to focus on behaviors that provide excitement and relief from a pointless life. It is this decision that then recruits the reward pathway, so that these behaviors provide a pathological hyper-motivation and excessive focus on a single activity.

This is important because it shows that we cannot treat compulsive behaviors like drug addiction. What people need to come out of these compulsions is not guilt-trips, twelve steps programs or medications like methadone, naltrexone or buprenorphine. What they need is another source of motivation, to expand the scope of their lives, to find meaning elsewhere.

Does pleasure decrease mental energy?

Circling back to the original question of this series of articles, the evidence I provided shows that sex and other forms of pleasure do not decrease our mental energy. Motivation and sustained effort are driven by the D2 receptors in the indirect pathway of the reward system and they are not downregulated by pleasure. In fact, some forms of pleasure, like exercise, playing or social interactions, increase the amount of D2 receptors and hence should increase our mental energy.

There is another problem with the ideas about dopamine in pop psychology. It is believed that pleasure produces ‘dopamine hits’. As we will see in the next article, this is not true. Dopamine does not cause pleasure.

Previous articles in this series

Does Sex Deplete Our Mental Energy? (Wix, Medium, Substack, Fetlife)

Pleasure Electrodes in the Brain (Wix, Medium, Substack, Fetlife)

Can dopamine be depleted from its synapses? (Wix, Medium, Substack, Fetlife)

Dopamine D2 Receptor Downregulation Is the Hallmark of Addiction (Wix, Medium, Substack, Fetlife)

References

Bauer EE, Buhr TJ, Reed CH, Clark PJ (2020) Exercise-Induced Adaptations to the Mouse Striatal Adenosine System. Neural Plasticity 2020:5859098.

Blum K, Sheridan PJ, Wood RC, Braverman ER, Chen TJ, Cull JG, Comings DE (1996) The D2 dopamine receptor gene as a determinant of reward deficiency syndrome. J R Soc Med 89:396–400.

Boileau I, Payer D, Chugani B, Lobo D, Behzadi A, Rusjan PM, Houle S, Wilson AA, Warsh J, Kish SJ, Zack M (2013) The D2/3 dopamine receptor in pathological gambling: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin and [11C]raclopride. Addiction 108:953–963.

Ceravolo R, Frosini D, Rossi C, Bonuccelli U (2010) Spectrum of addictions in Parkinson's disease: from dopamine dysregulation syndrome to impulse control disorders. J Neurol 257:S276–283.

Clark L, Boileau I, Zack M (2019) Neuroimaging of reward mechanisms in Gambling disorder: an integrative review. Mol Psychiatry 24:674–693.

Comings DE, Blum K (2000) Reward deficiency syndrome: genetic aspects of behavioral disorders. Prog Brain Res 126:325–341.

Comings DE, Rosenthal RJ, Lesieur HR, Rugle LJ, Muhleman D, Chiu C, Dietz G, Gade R (1996) A study of the dopamine D2 receptor gene in pathological gambling. Pharmacogenetics 6:223–234.

Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, Tschop MH, Lipton JW, Clegg DJ, Benoit SC (2008) Exposure to elevated levels of dietary fat attenuates psychostimulant reward and mesolimbic dopamine turnover in the rat. Behav Neurosci 122:1257–1263.

Dinardi JS, Egorov AY, Szabo A (2021) The expanded interactional model of exercise addiction. J Behav Addict 10:626–631.

Fagundo AB, Fernández-Aranda F, de la Torre R, Verdejo-García A, Granero R, Penelo E, Gené M, Barrot C, Sánchez C, Alvarez-Moya E, Ochoa C, Aymamí MN, Gómez-Peña M, Menchón JM, Jiménez-Murcia S (2014) Dopamine DRD2/ANKK1 Taq1A and DAT1 VNTR polymorphisms are associated with a cognitive flexibility profile in pathological gamblers. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 28:1170–1177.

Fisher BE, Li Q, Nacca A, Salem GJ, Song J, Yip J, Hui JS, Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM (2013) Treadmill exercise elevates striatal dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. NeuroReport 24.

Fournier L, Schimmenti A, Musetti A, Boursier V, Flayelle M, Cataldo I, Starcevic V, Billieux J (2023) Deconstructing the components model of addiction: an illustration through "addictive" use of social media. Addict Behav 143:107694.

Giuliano F, Allard J (2001) Dopamine and sexual function. International journal of impotence research 13:S18–S28.

Jonasson LS, Nyberg L, Axelsson J, Kramer AF, Riklund K, Boraxbekk C-J (2019) Higher striatal D2-receptor availability in aerobically fit older adults but non-selective intervention effects after aerobic versus resistance training. NeuroImage 202:116044.

Komisaruk BR, Beyer C, Whipple B (2006) The science of orgasm. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

MacRae PG, Spirduso WW, Walters TJ, Farrar RP, Wilcox RE (1987) Endurance training effects on striatal D2 dopamine receptor binding and striatal dopamine metabolites in presenescent older rats. Psychopharmacology 92:236–240.

Mas M, Gonzalez-Mora JL, Louilot A, Sole C, Guadalupe T (1990) Increased dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens of copulating male rats as evidenced by in vivo voltammetry. Neurosci Lett 110:303–308.

McCreary J, Metz G (2016) Environmental enrichment as an intervention for adverse health outcomes of prenatal stress. Environmental Epigenetics 2:dvw013.

Melis MR, Argiolas A (1995) Dopamine and sexual behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 19:19–38.

Melis MR, Sanna F, Argiolas A (2022) Dopamine, Erectile Function and Male Sexual Behavior from the Past to the Present: A Review. Brain Sci 12.

Nutsch VL, Will RG, Robison CL, Martz JR, Tobiansky DJ, Dominguez JM (2016) Colocalization of Mating-Induced Fos and D2-Like Dopamine Receptors in the Medial Preoptic Area: Influence of Sexual Experience. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience Volume 10 - 2016.

Olsen CM (2011) Natural rewards, neuroplasticity, and non-drug addictions. Neuropharmacology 61:1109–1122.

Paredes RG, Agmo A (2004) Has dopamine a physiological role in the control of sexual behavior? A critical review of the evidence. Prog Neurobiol 73:179–226.

Potenza MN, Voon V, Weintraub D (2007) Drug Insight: impulse control disorders and dopamine therapies in Parkinson's disease. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 3:664–672.

Robertson CL, Ishibashi K, Chudzynski J, Mooney LJ, Rawson RA, Dolezal BA, Cooper CB, Brown AK, Mandelkern MA, London ED (2016) Effect of Exercise Training on Striatal Dopamine D2/D3 Receptors in Methamphetamine Users during Behavioral Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:1629–1636.

Shen WW, Sata LS (1990) Inhibited female orgasm resulting from psychotropic drugs. A five-year, updated, clinical review. J Reprod Med 35:11–14.

Sulzer D, Cragg SJ, Rice ME (2016) Striatal dopamine neurotransmission: regulation of release and uptake. Basal Ganglia 6:123–148.

Trifilieff P, Martinez D (2014) Imaging addiction: D2 receptors and dopamine signaling in the striatum as biomarkers for impulsivity. Neuropharmacology 76 Pt B:498–509.

Trifilieff P, Feng B, Urizar E, Winiger V, Ward RD, Taylor KM, Martinez D, Moore H, Balsam PD, Simpson EH, Javitch JA (2013) Increasing dopamine D2 receptor expression in the adult nucleus accumbens enhances motivation. Molecular Psychiatry 18:1025–1033.

Tyler J, Podaras M, Richardson B, Roeder N, Hammond N, Hamilton J, Blum K, Gold M, Baron DA, Thanos PK (2023) High intensity interval training exercise increases dopamine D2 levels and modulates brain dopamine signaling. Frontiers in Public Health Volume 11 - 2023.

Uitti RJ, Tanner CM, Rajput AH, Goetz CG, Klawans HL, Thiessen B (1989) Hypersexuality with antiparkinsonian therapy. Clin Neuropharmacol 12:375–383.

Volkow ND, Morales M (2015) The Brain on Drugs: From Reward to Addiction. Cell 162:712–725.

Wise RA, Jordan CJ (2021) Dopamine, behavior, and addiction. J Biomed Sci 28:83.

Copyright 2025 Hermes Solenzol

Comments